Subtotal:

$1.95

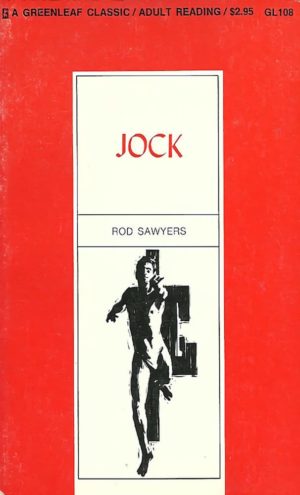

Category: Greenleaf GL

Tag: Dirk Vanden

Who Killed Queen Tom?

Greenleaf Classic

GL-106

Dirk Vanden

$2.95

GL-106 Who Killed Queen Tom?

Category: Greenleaf GL

Tag: Dirk Vanden

Who Killed Queen Tom?

Greenleaf Classic

GL-106

Dirk Vanden

$2.95

Related products

Introduction

There are times when the I whole thing seems like I’m remembering a book I read, a long time ago, or something someone told me once-the frightening things that happened to him one summer in Hollywood, California-things that changed his life totally. There are moments when it all comes flooding back over me, when I see something: a brick wall, or a certain street, an apartment house, a window with faded floral drapes, a quiet young man walking alone-then, suddenly, it is all happening again, and I duck my head and feel a wave of fear or anger or revulsion, just as I did then. And I hear a familiar whisper chanting:

You left your wife for a husband.

You traded her breasts for a pair of dimpled buttocks, And her cunt for a cock.

You were a square and you never really lived until you died.

And now you have found your freedom, And you are conforming again.

It’s as though there are two different people: myself now, and Tom Able then-although that is still my name, and the image in the mirror hasn’t changed (except it looks a little older now). I can go along, remembering it, thinking: Isn’t that interesting? Isn’t that frightening? Why doesn’t he do this or that, instead of what he is doing? Why doesn’t he realize what he’s getting into? But just as in a book, it happens the way it happens, and there’s nothing I can do about it now.

The first Thomas Able—Young Tom-was born and raised in Sacramento, California. His life seemed—to him (the way he arranged it carefully in his memory)—unremarkable. He was vaguely aware that “bad things” had happened to him, but somehow he had managed to store them away in the darkest corners of his brain so they would never come out to bother him-and perhaps they never would have, but for a stranger at a party; but for one of those “accidents” that happen that suddenly stop the stream of your life and send it in a completely different direction.

There are only a few things you need to know about Young Tom, and please forgive me for being brief; most of his life was dull and uninteresting, up to the time that his safe and peaceful world came crashing down around him: His father died when he was nine; his mother remarried several years later and had two more children, but they were so much younger than he, they seemed more like cousins than a brother and sister. There was always a feeling of distance between young Tom and the others in his family; his mother put it to the fact that “growing boys are like that,” and promptly ignored it. Tom knew it had something to do with his real father; he wasn’t sure why, but he knew there was a bothersome emptiness there. His mother was killed in an auto accident when he was twenty-seven; after that, after the funeral, he never saw his step-father or the children again.

He graduated from high school and almost immediately got drafted; on one of his leaves, he married the girl he had dated most of his senior year, Claire Worthington. When he received his orders to go to Germany (fortunately not Korea) Claire’s father arranged things so that she could go with him. It was in the Army that he stumbled upon what was to become his vocation—another “accident”. They had a Little Theater on the base, where the guys could involve themselves with something besides gambling and women, and Tom was drafted into one of the plays, as a favor to a buddy. (You should know this: Tom hated queers—gay boys, faggots, fairies, whatever else they were called, or called themselves—and all of the things they involved themselves in; drama had always seemed to him to be one of those. But in the Army, in Germany, none of the guys in the little theater group seemed to be “that way;” they seemed like nice, average, normal guys, like himself, and he fell in with them as though he had been born and raised backstage.) It wasn’t long before he had taken over the direction of all the plays. He had a natural talent for it.

When he returned to Sacramento, he decided to go to college, get his degree, and then go into teaching. He received his B.A. and was only four months short of his M.A. when Claire finally got pregnant. He applied for, and got (through the help of the head of the Theater Arts Department, “Doc”—Dr. John Bernard) a contract to teach at a new high school in Los Angeles (Sherman Oaks, in The Valley—but that’s Los Angeles).

He took his master’s in May, moved to Los Angeles in June, and started teaching when the school opened in September. John Jacob Ward High School, Sherman Oaks. He stayed there for ten years.

His first son, Cal (Leonard Calvin Able) was born in a drab little furnished apartment on Riverside Drive; his second, Gene (Eugene Patrick) came two years later, after they had saved and scraped together enough for a down payment on a small house near the school. Eventually they bought a larger home, up against the Hollywood Hills, on the valley side—not high up, because Claire hated those things they built on stilts that might wash down with the first good rain that came along. When the boys were old enough, (Cal was nine and Gene was seven) they decided they could build a pool without worrying about one of them falling in and drowning.

Tom’s attitude about life and people had softened (he called it “matured”) through the years. Reading, if not producing, plays such as Tea and Sympathy, Five Finger Exercise, The Killing of Sister George, and the others, along with the biographies of certain playwrights, had made him more inclined to “accept” sexual perversion as a condition of life—for some people-for some remote people—for people he would never meet or know; never, of course, for a friend or acquaintance, and certainly, definitely, never for himself.

I suppose we’re all like that to an extent. We rarely think of possibilities. When we start out on a trip, sometimes it passes through our minds that something might happen ; we might have an accident; someone might get hurt; so we make sure we take along the insurance cards, just-in-case. But we never believe anything could happen to us. Not us. Never!

There was a period in Tom’s life when he sat under an old-fashioned lamp (with a new dimestore shade) in an ugly little apartment, and played the “What If” game: A little less than a year before everything fell apart, he’d received a friendly letter from Doc, asking if he’d like to come back and teach at the college; a position was open. But there was the house, and the boys were in a good school, and moving would put them back near the relatives… But what if he had applied? And the night of the party, earlier in the afternoon, Claire had had a headache and they had considered staying home (neither really enjoyed going to faculty parties). What if they had not gone? What if they hadn’t got disgusted with the host and gone into the kitchen just when they did? What if that girl, at school, hadn’t got herself arrested? What if...? It’s a stupid game, and only useful if you happen to enjoy flagillating yourself like one of those monks.

Now it’s like reading a book. No matter how obvious it is that something is going to happen to the hero, no matter how often I say to myself, “The damned stupid fool! Can’t he see what’s happening?!” it doesn’t do a bit of good. The book is printed and no amount of sorrow or anger is going to change it.

He didn’t apply for the position. They did go to the party:

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.